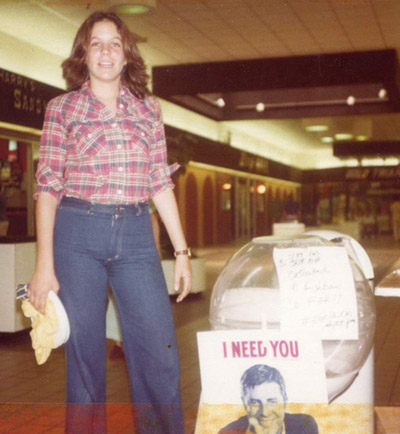

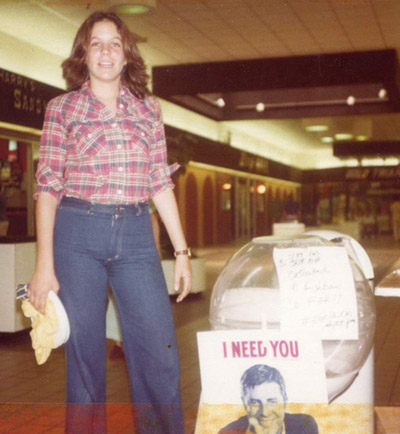

MDA Dance Marathon, 1979

Here it is! My very first podcast! I want to lay the ground work, a foundation, that provides an understanding of where I’ve been and what I’m most interested in doing. This episode is just me; future episodes will include conversations with others — people dealing with a chronic health condition, caregivers, as well as health practitioners of modalities some of us have found helpful. But basically — it’s all about maintaining a perspective of the Glass Half Full!

Transcript

Hello and welcome to my community. Well, I’m going to share a little about myself with you in this inaugural podcast and hopefully you’ll join me to become part of this community. Believe me, I don’t want to spend all this time talking with myself; I’d much prefer a conversation with another human.

And that’s what we’ll do for future episodes – I’ll have conversations with others. Friends, caregivers, and other people coping with a chronic health condition as well as practitioners and healers who have helped people develop positive coping tools. And eventually I hope you’ll become part of the conversation and community.

I’m Leslie Krongold – I live in Northern California and I’m originally from Miami, Florida. My journey has been a surprise; you don’t really think about health problems when you’re a teenager and young adult. You feel invincible…most of the time.

Saying I had a normal childhood really means little except in the context of now having a chronic health condition that shapes how and what I do every day…my health was generally good in my earlier life, though many of the minor anomalies I experienced now make sense as part of this slowly progressive genetic condition I have.

But, let me start with another part of the story and work backwards. I don’t relish telling my story. I’m more the type of person that poses questions to others asking about their story and I tend to take a back seat. But I feel my story is perhaps relevant for you to understand how I came to launch a podcast called GLASS HALF FULL and why you might want to join me for this part of the journey.

In my mid-30s I distinctly remember going out to lunch with a work colleague and as I grasped the door handle to get out of his car, my hand wouldn’t release its grip. I don’t think he noticed but I certainly did. It was odd and it harkened back to a memory from several years prior of my mother talking about difficulty with her wrists and grip.

My mother had many different ailments when I was growing up and spent time in hospitals for cataract surgery, gall bladder surgery, gastrointestinal stress, breathing anomalies…you name it. She also had a lifestyle of cigarette smoking and daily alcohol consumption that could have exacerbated her health. So, suffice it to say, I was neither on top of each medical diagnosis nor hospital visit she had since I lived across the country. She had told me about a muscle condition, which necessitated a visit to the University of Miami medical school where medical students observed her calf muscles; apparently one leg had less muscle tone than the other leg. I don’t recall her telling me it was a rare muscular dystrophy and I certainly didn’t hear that it was hereditary.

What I most remember is a phone call approximately 13 months before she died when my parents told me she had had a seizure, was rushed to the hospital, and eventually diagnosed with brain cancer, which metastasized from lung cancer. During those 13 months I visited a few times and talked with her frequently. My father never mentioned the doctors knew she would die within a year; I thought the radiation treatments and drugs were to help cure her. Of course this is nearly 25 years ago.

So when I reached for the door in my friend’s car and couldn’t quite release my grip, I remembered my mom. Now I can’t recall how soon after that experience I went to see a doctor. Maybe I had a few more experiences of difficulty releasing my handgrip but the way my memory works is like a project management software program. The lunch with the work colleague and getting out of his car in Menlo Park was a milestone.

The next point – if my life were to look like a GANT chart – is a visit with my HMO’s general practitioner. I had seen her maybe once or twice before. I probably thought she seemed like a good doctor with whatever minor issue I’d presented her.

After her cursory check of my hands and muscles she scheduled me for a blood work panel to see if I was nutritionally deficient. These tests came back negative. She then scheduled me for a visit to a neurologist. A neurologist?! A brain doctor? I don’t think my public school education included much study of human anatomy and my college study of filmmaking certainly didn’t cover neurology.

My memory of the next few steps is muddled – how many times did I see the neurologist until she had a definitive diagnosis? I’m not sure. That definitive diagnosis included a DNA test, which resulted in confirmation that I had a rare disorder called myotonic dystrophy. Seeing the results on paper didn’t emotionally penetrate me but the diagnostics leading up to the DNA test is what I most remember.

The EMG. The neurologist inserted a needle into several of my muscles – mostly different parts of my legs — to listen for extended bursts of electrical discharges that are indicative of abnormal electrical signals associated with slowing of muscle relaxation.

As I lay there in some uncomfortable paper gown, a specialist probed my body with needles & I heard these very disturbing sounds. The neurologist – a really young and super-smart woman – got excited. It must be like finding those key puzzle pieces to solve a mysterious puzzle. Eureka! I’ve identified your rare condition! And whatever words she used to explain this epiphany I don’t recall but I do remember a feeling of…your life is not what you expected it to be.

I stifled a few tears and wondered if she was aware of how this moment was impacting me.

I can’t remember whom I told…did I share this news with many friends at first? My every day life was essentially the same. I worked a lot. At that time I was an educational multimedia producer and my work life involved a lot of travel across the country. My father’s reaction to my diagnosis was a few notches short of empathetic. He claimed to have talked with doctors that reassured him I had nothing to worry about; my life would be normal.

I didn’t know anyone with myotonic dystrophy but I was aware that it was one of the many neuromuscular diseases covered by the patient advocacy organization – Muscular Dystrophy Association, or MDA. Who in America hadn’t grown up with the annual Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethon to raise money and awareness for children with neuromuscular disease? Children did seem to be the emphasis – Jerry’s Kids – didn’t exactly include the millions of adults beset with a diagnosis later in life.

In one of the several ironies in my life, I was already very familiar with the MDA. In grade school I was tempted to organize a carnival to raise money for MDA. The local television show of Skipper Chuck and his weirdo sidekick, Scrubby the sailor promoted backyard carnivals. I sent away for the carnival kit instructions and remember sharing them with neighborhood friends. We never did get the gumption to hold a fundraiser but later on in high school I made up for it.

In high school I threw myself into charity work conducted through the auspices of school service clubs. I would drive to the local MDA office in Miami, Florida to help with mailings – folding letters, addressing envelopes, licking stamps. Yes, I licked a lot of US postage stamps before the advent of adhesive stamps!

Soon after this initiation I organized two dance marathons at the local Skylake Mall to raise money for MDA. During one of the high school summers I was a camp counselor at the weeklong camp for children with muscle diseases. It was a 1:1 experience. At 16 years old I was responsible for taking care of a girl only two years younger than me that had a congenital condition that affected her both physically and cognitively. Back then I think the term – mental retardation – was still in vogue. It took me several years after my diagnosis to realize that young girl had the congenital form of myotonic dystrophy; talk about irony!

The camp experience was a turning point for me. Most significant were a few conversations I had with campers that were several years younger than myself – I’m not sure if I’m remembering their names accurately — Chris Leone and Susan Morse. I haven’t seen either of them since camp and it’s possible neither of them is still alive. These kids were so wise, so positive, so life-affirming. During that week one of the other campers died. I knew the young man; I’d become friendly with his counselor. This camp counselor experience was pivotal in my development as an empathetic adult.

So here I was in my mid-30s diagnosed with a progressive muscle disease and I naturally thought of my prior experiences with this patient advocacy organization. I called their local office in northern California, registered with them, and found out about their monthly support group meetings.

Again my memories are not clear but the Internet did exist when I was diagnosed and I certainly Googled my diagnosis. I’m not sure when I came upon the graph – I’ll tell you more about the graph but for now let’s just call it The graph. I can’t say I learned very much about the condition from the Internet at that time. The MDA had some information about the multi-systemic nature of myotonic dystrophy and its slow progression. There were photos of men with the condition – balding men with long, thin faces, hollowed cheeks and temples, wasted arm and leg muscles. It wasn’t pretty. At that point I had no obvious physically identifying characteristics of the condition. And all the black and white photos showed these men from an earlier era; it was easy to distance myself from this.

It was the graph I found on some academic website; the graph was part of a medical journal article assessing the average life span of someone diagnosed with my condition. The graph was organized by the genetic identifier – the CTG count from the DNA blood test I had. CTG is a trinucleotide located on a specific chromosome. The trinucleotide normally repeats for all humans but when it has expanded repeats it signifies the presence of the condition.

Healthy people have up to 50 CTG repeats. Children with the congenital form of the condition may have 1,000 or more CTG repeats. I had approximately 500 repeats, which was defined as classic adult-onset. According to the graph, my life expectancy was between 48 – 55 years.

Did I cry myself to sleep the evening after I discovered this online graph? I’m not sure; I think it had a delayed impact on me. The data would haunt me intermittently; it was a battle between my rational and irrational mind. I knew there could be no crystal ball and there were always statistical outliers. For now I kept my diagnosis and fearful thoughts to myself and limited my disclosure to others. But I did attend the MDA support group meeting.

I knew little about support groups. Individual psychotherapeutic counseling was familiar to me. I had friends involved in 12-step programs. But until that point I knew little if anything about support groups.

The meeting took place in the early afternoon on a weekend at a local hotel’s small conference room. The table was long and rectangular; most attendees were seated in chairs though a few people were in wheelchairs or using other assistive mobility devices. This didn’t unnerve me though I’ve heard it does freak others out when they first attend a support group meeting for their chronic health condition. It’s that visual of what the future may hold – reliance on a device, weakness…I think I was more filled with curiosity than fear.

People were pleasant at the meeting though the facilitator – a middle-aged woman with a neuromuscular condition — made little effort to find out more about me. I was struck by how much her personality and personal story dominated the meetings. It didn’t surprise me that after a few sessions she decided to leave the organization due to facilitator burnout. What was a surprise was MDA’s request that I sign on as the meeting’s next facilitator.

The liaison between the MDA office staff and the actual support group meeting is a person with the title Health Care Services Coordinator. This role was often filled by an eager recent college grad that would end up leaving the organization within a year because it is an incredibly stressful job for a young person. This coordinator got to know me a little but I saw nothing in my background that would have assured her that I was the right fit. But, she changed my life…and for that, I am forever grateful. If only I could remember her name and thank her personally.

And 17 years later here I am. But there’s more to this story. I just wanted to acknowledge that this is another milestone for the GANT chart of my life. Duly noted, I hope.

Do I remember the first support group meeting I facilitated? Not one bit. I may have notes for it in a file somewhere. What I do remember is MDA gave me nothing to prepare myself. There was no guide on how to facilitate a support group, no training, nada! I did have teaching experience – middle and high school as well as community college experience. I was an educator and that’s how I approached this gathering of adults with a shared diagnosis of a chronic health condition.

I’d like to make a distinction now between a chronic and acute health condition. Many conditions may begin as acute – there’s an urgent need to take care of something wrong, an imbalance. And perhaps there’s success with bringing the body back into balance. But for many of us with health conditions where there is no cure or treatment, we engage in a continuous challenge to maintain balance of a chronic condition. And with this perspective I assume much of life for many humans is just that – a continuous challenge to maintain balance. So although I view the target audience for this podcast as others coping with a chronic health condition, I know there are caregivers as well as others who are trying to maintain a healthy balance in life with an optimistic Glass Half Full perspective.

Back to support groups. I have learned so much from this path – meeting people of diverse life experience, ethnic, racial, religious, and cultural affiliations, and diverse socio-economic and educational backgrounds. Had I not had this support group connection for the last two decades I don’t know if I would have met so many wonderful and different people? I can’t possibly summarize what I’ve learned in this first podcast but I hope to continue learning and sharing and growing a community with you.

Let’s go back to my diagnosis and life after taking on the role of a support group facilitator. I continued to work at my job for a while until I got sick. I’d been getting sick frequently with the long hours and constant work travel; arriving home after work and napping on the couch for a while. But I see another milestone being this one day I had to be in Monterey for a work meeting. Every month I would make the two hour trip to meet with team members in Monterey. It was the same routine – come in the night before, sleep in a local hotel, and spend the next day in meetings. The hotel’s air-conditioning system wasn’t working and I had a rather sleepless night. I was listless during the meetings and ended up leaving for home earlier than usual. My car’s air-conditioning system wasn’t working well either and I had to stop frequently on the drive home to get water and use the restroom. By the time I got home I was completely wiped out. Physically I was exhausted and very weak. My heart was racing. The anxiety had kicked in but I wasn’t aware of the difference between the actual physical symptoms and the symptoms from the anxiety. I called 911 and was brought to the hospital ER. Once there I told them about myotonic dystrophy and they didn’t know what it was. I just wanted to sleep – after I threw up a few times – and they released me in the middle of the night without a diagnosis. Was it heat exhaustion? Food poisoning? I don’t know.

The next few days I realized my body was not able to handle the same stress it had been under for years. You know, the normal stressors of life — making a living, moving up the career ladder. Shortly after this hospital incident, I left my fulltime job to pursue freelance contract work where I felt I could have more control over my life. This wasn’t an easy decision to make but I felt so lousy I couldn’t think of different options available to me.

This may have been a time to explore other options – discuss my health condition with my employer, take a short disability leave…I wasn’t in a frame of mind to imagine other possibilities. I just wanted to get out. And I did.

The next ten years were interesting. I had more time to explore other healing modalities for myself as well as brining in guest speakers for the support group meetings. Some of the modalities I was already fluent with — yoga for example. Not long after college I began taking yoga classes and learning about yoga. It’s not just poses like downward dog. I can remember some of the first times I did poses with twists and my body would react in a healthy cleansing sort of way. It’s a difficult sensation to describe because its subtle but practicing yoga helped me physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

At support group meetings I was introduced to acupuncture. A local acupuncture college sent student practitioners to one of our meetings to do a presentation. Since it’s a teaching college they had incredibly inexpensive treatment options so I went down that path and learned more about my body and diet.

Every month at the support group there was more to learn – not just with alternative modalities but also from western-trained physicians and health care professionals such as physical, occupational, and respiratory therapists. It was fascinating to see how their presentations changed over 17 years. One physical therapist in particular – a very popular and well-liked woman – would garner a large audience. She’d demonstrate a variety of physical movements for different types of people given whatever their mobility challenge was. The last time she spoke with our group – maybe about two years ago – she ended the session sharing with us her experiences with meditation and mindfulness. This was a real departure from her usual presentation and proof that times have certainly changed!

The support group meetings included all types of information. Pragmatic information brought to us from federal and regional agencies such as the

- Social Security Administration, In-Home Health Services, and Department of Rehabilitation

- Nonprofit organizations specializing in training and providing service animals

- Researchers discussing the process for inclusion in clinical research trials.

- And, Demonstrations of food preparation for dysphagia – swallowing difficulties – to name just a few.

As I got to know the people attending my support groups I realized how much knowledge and wisdom many of them had. I’m a strong believer in empowering people so several sessions had support group participants take the lead and share what expertise they had developed.

One man who had been using a wheelchair for many years talked with us about navigating the various modes of public transportation. For many people who eventually need to use a wheelchair for their own safety in public, the entire process can be daunting. Another group participant gave us a presentation about working with a private athletic trainer who grew to understand more about her condition. Several other participants became savvy travelers and taught us how to arrange for the safest and most expeditious airport experience, how to secure accessible hotel rooms, and which foreign countries are the most accessible.

Over the years the support group experience became a bigger part of my life. I worked part-time, learned more about my changing body, and shared what I was learning with my support groups; at some point I acquired a second support group that met in a different city.

When you have a chronic health condition you can’t help but spend more time managing your physical and emotional health. Your life trajectory changes. Your peers are climbing the career ladder, raising their children, and you’re weighing the options for dealing with weakness and fatigue. Although my condition has no treatment there are a variety of pharmaceuticals many of my friends take to manage some of their symptoms. I repeatedly have chosen not to take any pills beyond the occasional Tylenol for body pain.

I’m not sure why I’m like this; perhaps it’s a reaction to the numerous drugs and treatments I witnessed my mother and other relatives take? I’ve chosen to manage my symptoms through diet, exercise, attitude, and a nightly hot bath.

This works for me and I will continue this path for as long as I can. I can’t say any one thing I do is the silver bullet but with more control over my daily life I’m happy to say that I’ve not had another ER visit.

The support groups I’ve facilitated have been open groups – each month would bring several core members who have become like family to me – but we’d also have new people attend. Maybe they were newly diagnosed or after several years since a diagnosis they were at a point where they needed to reach out. I’ve met hundreds of people through these groups and in 17 years I’ve seen a lot of variety. The negative experiences are minimal but they did stand out and I learned from them as well.

What I’ve been most struck by are people who refuse to change anything in their lifestyle. They’ll openly speak about the misery they’re experiencing be it body pain, gastrointestinal discomfort, weakness, and/or emotional issues. And they’re stuck…unable to examine their diet and lifestyle to see if something is within their power to change. For example, there was a middle-aged man that attended the group for a few months who told us about his constant GI stress where he often could not leave his house; he couldn’t be away from a bathroom. Upon further questioning I discovered he drank soda all day and the majority of his diet was processed food. I am not one to admonish and I don’t dole out advice but as a group we did talk with him about making gradual dietary changes. He was completely resistant.

Every once and awhile there would be a visitor to the group with a similar attitude — and I began to wonder why are some people able to make incremental changes in their behavior – see positive results as feedback – and adjust their lifestyle accordingly, and others aren’t able to do this?

Obviously there are no easy answers here but I wanted to explore this area. During this time I was also working on small projects for different departments at a local medical school. Research projects for a variety of audiences – teaching children at an elementary school how to practice good oral health, advising dentists on how to identify victims of domestic abuse, and helping low-income adults with diabetes type 2 make healthier food choices.

I decided to return to school to pursue a doctorate degree in education and my line of research explored the role of support group facilitators and how they promote social support and self-management health behaviors in the context of a support group. During this time I read as much of the previous research literature I could – studies predominantly included people with more common health conditions – diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease – very few of the studies were with people with neuromuscular disease let alone myotonic dystrophy. But I saw so many similarities for people with chronic illness.

After facilitating my own support group for many years I finally had an opportunity to see how other support groups operate. For a qualitative research course I was able to visit and observe support groups for adults with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and ALS. For my dissertation I worked with two national multiple sclerosis patient advocacy organizations and surveyed over 300 facilitators of MS support groups across the country. I won’t take this time now to go deeper into my research findings but I will share bits of it when appropriate during future podcast episodes.

At some point during my research I realized I wanted to work with support group facilitators. And that’s what I had an opportunity to do for these last four years. At the myotonic dystrophy foundation, another patient advocacy organization, I was able to launch support groups throughout the U.S., Canada, and Switzerland and train over 30 people to become support group facilitators. It was an amazing experience.

So, what about this Glass Half Full thing you may be wondering? It’s the next chapter in my life. I want to continue doing what I’ve done, learn more, reach out to more people to share how life with a chronic health condition can be challenging but how one can continue to lead a life of quality and integrity.

I’m certainly not the only one to choose to have a Glass Half Full perspective. I’ve been fortunate to meet many people – men and women, of all ages, of all backgrounds – who in spite of a physical and/or emotional challenge have adapted new ways to live and they’ll share their passion and ways of coping with us. I’ll also meet with people and organizations engaged in alternative healing modalities – disciplines – that either I or someone close to me has explored with positive results.

Some of the areas I’ve explored include diet, yoga therapy, acupuncture, Pilates, aromatherapy, meditation, and qigong. But that’s just me. Let’s hear about what works for you? What helps you maintain a Glass Half Full perspective?

I hope you’ve heard something during this first podcast that has whet your appetite and inspires you to keep tuning in. I invite you to become part of the conversation and community by visiting our website: Glass Half Full dot online and the Facebook page for Glass Half Full Online.

Thanks for listening…

A Gantt chart is a type of bar chart developed by Henry Gantt in the early 1900s, that illustrates a project schedule.

Electromyography, is an electro-diagnostic medicine technique for evaluating and recording the electrical activity produced by skeletal muscles.

Which refers to of a disease or physical abnormality that is present from birth.

In statistics an outlier is an observation, or value, that lies at an abnormal distance from the other values in a random sample from the population.

Social Support is a general term used to describe five different types of support offered in a social setting. These are: Information support is any communication offering suggestions or guidance, referral to an expert, book, or website, or sharing personal experience. Tangible assistance is any communication or act providing direct or indirect tasks, a loan, or willingness to assist in some capacity. Esteem support is any communication offering a compliment, validation, or relief of blame. Network support is any communication providing access to others that are part of the immediate social network. And Emotional support is any communication or act expressing care and concern.

Self-management health behaviors are a set of behaviors to help a person manage their own illness. Some of those behaviors include diet, exercise, and relaxation techniques.

This week’s guest is Melissa Marshall. We’ve known each other since elementary school. And guess what? She wrote “the cancer fight song!”

This week’s guest is Melissa Marshall. We’ve known each other since elementary school. And guess what? She wrote “the cancer fight song!” Ted Abbott is making his dreams come true in Virginia. He started a nonprofit organization,

Ted Abbott is making his dreams come true in Virginia. He started a nonprofit organization,  My first conversation is with a dear friend, Laurel Roth Patton. Laurel talks with me about her diagnosis with bipolar condition and shares some of the most useful tools she’s gathered over the years. Please visit Laurel’s

My first conversation is with a dear friend, Laurel Roth Patton. Laurel talks with me about her diagnosis with bipolar condition and shares some of the most useful tools she’s gathered over the years. Please visit Laurel’s